Missouri Trails To The Past

St. Louis Arsenal

St. Louis Arsenal (1827-Present) - A large complex of military

weapons and ammunition storage buildings owned by the United

States Army, the arsenal, which was built in 1827, is still

utilized today. In 1825, the arsenal was located at Fort Belle

Fontaine some 15 miles north of St. Louis, but the old fort and

its small arsenal were falling into disrepair. Additionally, the

War Department felt like it needed a bigger facility and began

making plans to build a new one.

St. Louis Arsenal (1827-Present) - A large complex of military

weapons and ammunition storage buildings owned by the United

States Army, the arsenal, which was built in 1827, is still

utilized today. In 1825, the arsenal was located at Fort Belle

Fontaine some 15 miles north of St. Louis, but the old fort and

its small arsenal were falling into disrepair. Additionally, the

War Department felt like it needed a bigger facility and began

making plans to build a new one.

A new site was selected on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River by Lieutenant Martin Thomas. The 37- acre site was was advantageous for its strategic view, access to the river, and its proximity to the main area military base -- Jefferson Barracks. In 1827, the first building on the new arsenal grounds was completed but, it would be a year before it would actually store the ammunition. In the meantime, Fort Belle Fontaine continued to supply ammunition and military supplies to troops operating in the Louisiana Territory until June 1828.

When the St. Louis Arsenal began to store the ammunition and supplies, Fort Belle Fontaine was abandoned. The new St. Louis Arsenal grew to house a large three story brick building, an armory, an ammunition plant, and several wagon repair shops. By 1840, 22 separate buildings had been erected, and a garrison of 30 ordnance soldiers manned the site, along with 30 civilian employees, who assembled finished weapons and artillery.

When the Mexican-American War erupted in 1846, the arsenal was very busy producing small arms, ammunition, and artillery and increased its civilian workers to some 500 men. During the war, the arsenal 19,500 artillery rounds, 8.4 million small arms cartridges, 13.7 million musket balls, 4.7 million rifle balls, 17 field cannon with full attachments, 15,700 stand of small arms, 4,600 edged weapons, and much more. When the war was over, the civilian staff was reduced to about 30 and the arsenal was relatively quiet for about a decade until the Utah War began in 1857. Civilian staff was once again increased, this time to about 100 civilians.

Prior to the Civil War, a number of congressmen, anticipating secession, began to demand that their quota of arms and ammunitions to be shipped from the St. Louis Arsenal to state armories and arsenals. In December, 1860, President James Buchanan's Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, a Virginian, was accused of aiding in the transfer of arms to southern states. He quickly resigned his post and returned to Virginia. Afterwards, an investigation was conducted into his involvement, where it was found that he had bolstered the Federal arsenals in some Southern states by over 115,000 muskets and rifles in late 1859. He had also ordered heavy ordnance to be shipped to the Federal forts in Galveston Harbor, Texas and to Fort Massachusetts in Mississippi. Though he was officially cleared of any wrong doing, many continued to suspect that his involvement had helped arm the Confederate States of America in preparation of the Civil War.

By early 1861, the Civil War was looming and the states were choosing sides. Missouri was caught in the middle as most of its residents supported slavery. Despite this, the Missouri Constitutional Convention of March, 1861 voted to stay with the Union, but refused to supply men or weapons to either side if war broke out. This resulted in a state of war within its own borders between the U.S. Army and Missouri> citizens and the St. Louis Arsenal would become a primary target.

In March 1861, General Nathaniel Lyon arrived in St. Louis to command of Company D of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. At the that time, Missouri Governor Claiborne F. Jackson was a strong Southern sympathizer, as were many of the state legislators. Lyon was accurately concerned that Jackson might try to seize the federal arsenal in St. Louis if the state seceded and that the Union had insufficient defensive forces to prevent the seizure.

One of Lyon's first objectives was to strengthen the arsenal defenses, but he was opposed by his superiors, including Brigadier General William S. Harney of the Department of the West. However, Lyon soon requested the aid of General Francis P. Blair, who agreed that southern leaders might try to carry neutral Missouri into the Confederate movement. Lyon was soon named commander of the arsenal and General Blair formed a secret paramilitary group of some 1,000 men called the Wide Awakes.

On April 20, 1861, a pro-Confederate mob at Liberty, Missouri seized the only other arsenal in the state -- the Liberty Arsenal. The Southern sympathizers captured about one thousand muskets, four brass field pieces and a small amount of ammunition. It was the first civilian Civil War hostility against the Federal government in the State.

In response, Lyon armed the Wide Awake units and on April 29th, secretly sent all but 10,000 rifles and muskets to Alton, Illinois. A few days later, on May 10th, he directed the Missouri volunteer regiments and the 2nd U.S. Infantry to capture a force of Missouri State Guards stationed at Camp Jackson in the suburbs of St Louis with the intention of seizing the arsenal. Federal troops surrounded and captured the camp, forcing its surrender. Though Lyon's actions gave the Union a decisive initial advantage in Missouri, it also inflamed secessionist sentiments in the state.

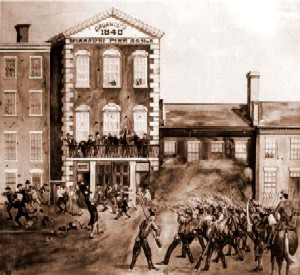

After capturing

the force of Missouri State Guards, Lyon marched them through

the streets of St. Louis to the Arsenal. This lengthy march was

widely viewed as a public humiliation for the state forces, and

immediately angered citizens who had gathered to watch the

commotion. Before long, riots broke out as Missouri citizens

hurled rocks, paving stones, and insults at Lyon's troops. When

a pistol was fired into their ranks, fatally wounding one Union

soldier, the federals fired into the crowd, killing some 20

people, some of whom were women and children, and wounding as

many as 50 more. Known as the "St. Louis Massacre, the incident

sparked several days of rioting that was only subdued with the

installation of martial law and the arrival of Federal Regulars.

The highly publicized affair further increased the tension in

the border state of Missouri.

After capturing

the force of Missouri State Guards, Lyon marched them through

the streets of St. Louis to the Arsenal. This lengthy march was

widely viewed as a public humiliation for the state forces, and

immediately angered citizens who had gathered to watch the

commotion. Before long, riots broke out as Missouri citizens

hurled rocks, paving stones, and insults at Lyon's troops. When

a pistol was fired into their ranks, fatally wounding one Union

soldier, the federals fired into the crowd, killing some 20

people, some of whom were women and children, and wounding as

many as 50 more. Known as the "St. Louis Massacre, the incident

sparked several days of rioting that was only subdued with the

installation of martial law and the arrival of Federal Regulars.

The highly publicized affair further increased the tension in

the border state of Missouri.

Later, General Nathaniel Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson's Creek on August 10, 1861. The St. Louis Arsenal remained in Federal hands throughout the Civil War, and, with St. Louis firmly in Union control, provided substantial quantities of war materiel to the armies in the Western Theater.

When the Civil War was over, the arsenal again became relatively quiet. In March, 1869, ten acres of the arsenal grounds were given to the City of St. Louis for the creation of Lyon Park, named for General Nathaniel Lyon. Two years later, in 1871, it was determined that the ammunition could be better secured at Jefferson Barracks and the supplies were transferred, though the arsenal grounds were retained by the U.S. Army.

Later, the arsenal complex was transferred to the United States Air Force and the Department of Defense. Today, it continues to serve as an active military reservation, housing a major branch of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

Today, the vast majority of the St. Louis Arsenal and grounds are closed to the public. Visitors and cameras are not allowed inside the complex, but you can still visit a part of the arsenal that is open to the public. Nearby is Lyon Park, located near the intersection of South Broadway and Arsenal Streets.